Sunday, 25 March 2018

Sunday, 4 March 2018

22:30

22:30 SANKET MARSKOLE

SANKET MARSKOLE No comments

No comments

Friday, 14 October 2016

04:36

04:36 SANKET MARSKOLE

SANKET MARSKOLE No comments

No comments

Collegiate shag

The Collegiate Shag (or "Shag") is a partner dance done primarily to uptempo swing and pre-swing jazz music (185-200+ beats per minute). It belongs to the swing family of American vernacular dances that arose in the 1920s and 30s. It is believed that the dance originated within the African American community[1] of the Carolinas in the 1920s,[2][3] later spreading across the United States during the 1930s. The shag is still danced today by swing dance enthusiasts worldwide.From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia(Redirected from Collegiate Shag)

Contents

The Steps

In the 1930s "shag" became a blanket term that signified a rather large family of jitterbug dances (swing dances) that all shared certain characteristics. The most notable of these characteristics are (1) a pulse that's consistently held up high on the balls of the feet (a.k.a. a "bounce" or "hop" to match every beat in the music) and (2) footwork with kicks that reach full extension on the off-beat (even beats) rather than the on-beats (odd beats) as with most other dances that were popular at the time. Dance instructors from the swing era often grouped the different shags into three rhythmic categories: single rhythm, double rhythm, and triple rhythm shag.[4] The different names are intended to denote the number of 'slow' steps (e.g., a step, hop combination) performed during each basic. The slow steps were then followed by two 'quick' steps (e.g., a step, step combination).

Today, shag enthusiasts and swing dance historians also recognize an additional shag rhythm that has come to be known as "long double-shag".[2][5] This rhythmic variation is identical to double-shag except that it has four quick steps rather than two. It has been traced to Charlotte, NC, at least as far back as 1936, where it co-existed with the triple and single-rhythm variations.[6] It is commonly believed that double-rhythm shag evolved somewhat later than the others, originating in either New York or New Jersey in the mid-1930s.[2] And, though double-shag is the most popular form of collegiate shag today, single-rhythm shag is believed to have been the dominant rhythmic pattern during the swing era.[4]

Described below is double-rhythm shag, which uses a "slow, slow, quick, quick" pattern. And unlike the other three rhythmic patterns, which all have eight or sixteen counts in their basic, the double-rhythm basic has six counts.

The basic step is danced in a face-to-face ("closed") but offset position (i.e., the lead and follow are chest to chest, but their orientation to one another is offset in such a way that the feet are not toe-to-toe but alternate like the teeth of a zipper). Partners stand close, with the lead's right hand positioned on the follow's back. The follow's left arm then rests either on the lead's shoulder or draped around his neck.

It was also common for partners to have an exaggerated hand-hold (i.e., the way the lead's left hand and arm are positioned as he hold the follow's right hand) where the arms are held high in the air. Depending upon the height of each partner, the couple may have their arms pointed straight up. This was not always practiced, but it is understood to be one of shag's distinctive features. Some dancers prefer to hold the arms much lower, similar to conventional ballroom positioning. Finally, the follow's footwork usually mirrors the lead's.

Note: Step (in the description below) is defined as: a weight shift to the opposite foot while hopping (this is usually minimal; almost more of a slide than a literal hop). Hop is defined as: a lift-and-plant motion on the same foot. The planted foot is the foot with the dancer's weight on it.

- The Shag Basic: (from the lead's point of view) Beat 1: STEP onto left foot, beat 2: HOP on left, beat 3: STEP onto right foot, beat 4: HOP on right, beat 5: STEP onto left foot, and beat 6: STEP onto right foot. The movement during beats 5 and 6 is often described as a shuffling motion. As mentioned above, this is usually broken down verbally as "slow, slow; quick, quick" where the 'slows' cover two beats (or 'counts') each and the 'quicks' mark a single beat (or 'count') each. Hence, for the lead this would be two counts with the weight on the left leg while the right leg moves, two counts with weight on the right leg while the left leg moves, followed by a quick step onto the left and then a quick step onto the right. The follow's movement would be the exact opposite.

- Cross Kicks: (done with the partners positioned side-by-side) the same movement as the basic but where the non-planted foot kicks on each slow, and where the quick-quicks are done with one foot behind the other (in tandem).

- Breaks (a.k.a. Shag Dips): A step and hold action where the non-planted leg is extended fully and the planted leg is bent underneath the dancer for support (hop onto left, leaving out the step; hop onto right, leave out the step; step left and step right)

- The Basic Shag Turn: it is customary for most turns in shag to be executed on counts 5 and 6 (i.e., the quicks-quicks). The most common turn is executed from closed position on the last two beats of the basic (5–6) with the follow traveling clockwise. The lead executes this by using his right hand (on the follows back) to lead her to turn on counts 5 and 6. Partners then return to closed position on the first count of the next basic. [Apache (a.k.a. "Texas Tommy") turns are also common in shag.]

Name

"Shag" itself (when used in reference to American social dances) is a very broad term used to denote a number dances that originated in the first half of the 20th century. Today, the term "collegiate shag" is often used interchangeably with "shag" to refer to a particular style of dance (i.e., the dance covered in this article) that was popular amongst American youth during the swing era of the 1930s and 40s. To call the dance "collegiate shag" was not as common during the swing era as it is today, but when the "collegiate" portion was tacked on (as it was with other vernacular dances of the time) it was meant to indicate the style of the dance that was popular amongst the college crowd.

The identification of a particular variant as 'collegiate' probably had its roots in a trend that sprang up in the mid-1920s, where collegiate variations of popular dances began to emerge. These included dances like the collegiate Charleston, collegiate rumba, collegiate one-step, collegiate fox trot, etc.[7][8] These forms employed hops, leaps, kicks, stamps, stomps, break-away movements, and shuffling steps. The name "collegiate shag" became somewhat standard in the latter part of the 20th century (see swing revival), presumably because it helped to distinguish the dance from other American vernacular dances that share the "shag" designation. Carolina shag, which evolved from a dance called the Little Apple,[2] and St. Louis shag, which is believed to have been an outgrowth of the Charleston, both adopted the name shag—though neither one of them is directly related to the shag that's the focus of this article.[2]

History

Unfortunately, shag's origins are not very clear. Descriptions of the dance in literature from the time period suggest it began in the South[9] as a 'street dance', meaning it did not initially evolve as part of the curriculum taught by a dance master or in a dance studio. Nevertheless, a particular version of the shag was eventually adopted by the Arthur Murray studios where it was standardized in the late 1930s.[2]

Publications from the era testify to shag's popularity throughout the country during the 1930s. They also clue us into the fact that, despite its enormous popularity, the dance itself wasn't universally known by the name "shag", which only makes tracing its origins more difficult. Arthur Murray's book Let's Dance reports that shag was known throughout the United States under various names, like "flea hop".[10] And by the late-1930s there were arguably a hundred or more stylistic variations of the dance.[11]

In the 1935 book entitled Textbook of Social Dancing, Lucielle and Agnes Marsh tell us that, "At the most exclusive Charleston Colonial Ball we found the debutantes and cadets doing what they call the Shag. This is a daring little hop and kick with sudden lunges and shuffling turns. As we followed our survey through the South we found the same little, quick hop, skip, and jump under the names of Fenarly Hop and Florida Hop. Through the West the same steps could be traced under the names of [the] Collegiate, Balboa, and Dime Jig."[12] And a New York writer sent to Oklahoma in late 1940 noted an "...Oklahoma version of shag done to the western swing music of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys at the Cain's Dancing Academy in Tulsa."[13]

The earliest known reference to a dance called "shag" can be found in a book entitled The Land of the Golden River by Lewis Philip Hall, published in 1975. In this book, the author claims to have invented a dance he named "the shag" in 1927. Hall tells us that he and his dance partner[14] introduced the dance at the second annual Feast of Pirates festival in Wilmington, N.C. in 1928.[15] But there is reason to believe that what Hall and his partner came up with was not the same dance that became so popular amongst the swing dance circles of the late 1930s and 40s.[16]

As the section above points out, the naming practices of the time were often inconsistent. Two dances with the same name may not necessarily share the same origin story or even look alike. Carolina shag and St Louis shag, two dances that both became popular in the late 1940s and 50s, provide a perfect example of this complication. Both came to be called "shag", though they have very different origin stories. So, although it is possible that the dance that Lewis Hall and his partner invented somehow gave rise to the shag of the swing era (i.e., what we call "collegiate shag" today), this possibility could also be granted to a number of other seemingly unrelated dances from the late 1920s or early 1930s, some of which might not have even been called shag.

Like Charleston (dance) and Big Apple (dance), the shag originated among African Americans[17] in the 1920s, where again, it may or may not have actually been called "shag".[18] Even the step 'invented' by Lewis Philip Hall was, according to author Susan Block, "...mostly gleaned from African American dances...".[19]

It has also been suggested that the dance evolved from a partnered version of the solo Vaudeville/tap step called "flea hop", which featured a movement pattern that's very similar to shag [Citation Pending]. This view may be strengthened by the fact that, in the late 19th century, "shagger" was a nickname for 'Vaudeville performer'.[4] Perhaps this Vaudeville slang was what inspired Lewis Hall to give his dance the name "shag".

Related Pages

References

- ”Nice People Suddenly Get the Urge to Become Vulgar” The Afro American 14 June 1941. 1[Research credit: Ryan Martin]

- The Rebirth of Shag. Dir. Ryan Martin. Vimeo. 2014 <http://vimeo.com/88253085>.

- “Shag Latest Dance” Blytheville Courier News (Arkansas) 25 July 1929: 5 [Research credit: Forrest Outman]

- Lance Benishek. Interview.The Rebirth of Shag. Dir. Ryan Martin. Vimeo. 2014 <http://vimeo.com/88253085>.

- The rhythmic variations described here were not unique to shag. See Clendenen, F L. Dance Mad or the Dances of the Day. St. Louis, Mo: Arcade Print Co., 1914. and McDougall, Thomas. "The Foxtrot: And other Gossip from the States." Dancing Times. Oct. 1914.

- Jean Foreman. Interview.The Rebirth of Shag. Dir. Ryan Martin. Vimeo. 2014 <http://vimeo.com/88253085>.

- Ernest E. Ryan School of Dancing. Advertisement. American Dancer 1 June 1927: 4. Print.

- Collegiate Dance. Advertisement. Jefferson Herald 14 June 1928: 8. Print.

- Wright, Dexter and Anita Peters. How to Dance. The Blakiston Company, 1942. 187.

- Murray, Arthur. Let's Dance. S.l.: Standard Brands Inc, 1937. 27.

- Powell-Poole, Helon. "The Carolina Shag." American Dancer, Jan. 1936: 13. Print.

- Marsh, Agnes L. Textbook of Social Dancing. New York: Fischer, 1935. preface pg VI.

- San Antonio Rose – The Life and Music of Bob Wills. Charles R. Townsend. 1976. University of Illinois. 198. ISBN 0-252-00470-1

- In the literature, Hall refers to his partner as "Julia", though it is inferred that this was not her real name.

- Hall, Lewis P. The Land of the Golden River. Wilmington, N.C. Wilmington Press, 1975. 143–44[Research credit: Peter Loggins]

- Cameron, Kathrine Meier. Interview. The Rebirth of Shag. Dir. Ryan Martin. Vimeo. 2014 <http://vimeo.com/88253085>.

- ”Nice People Suddenly Get the Urge to Become Vulgar” The Afro American 14 June 1941. 1[Research credit: Ryan Martin]

- Lance Benishek and Jean Foreman. Interviews. The Rebirth of Shag. Dir. Ryan Martin. Vimeo. 2014 <http://vimeo.com/88253085>.

04:33

04:33 SANKET MARSKOLE

SANKET MARSKOLE 1 comment

1 comment

East Coast Swing

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

East Coast Swing (ECS) is a form of social partner dance. It belongs to the group of swing dances. It is danced under fast swing music, including rock and roll and boogie-woogie.This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Yerrington and Outland equated East Coast Swing to the New Yorker in 1961. Originally known as "Eastern Swing" by Arthur Murray Studios, the name East Coast Swing became more common between 1975 and 1980.[1]

Contents

History

The dance was created by dance studios including the Arthur Murray dance studios in the 1940s, based on the Lindy Hop. Lindy Hop was felt by dance studios to be both too difficult and too unstructured to teach to beginning dancers, but there was market demand for training in Swing Dance. The dance studios had initially dismissed Lindy Hop in particular as a fad.[2] East Coast Swing can be referred to by many different names in different regions of the United States and the World. It has alternatively been called Eastern Swing, Jitterbug, American Swing, East Coast Lindy, Lindy (not to be confused with Lindy Hop), and Triple Swing.[3] Other variants of East Coast Swing that use altered footwork forms are known as Single Swing or "Single-step Swing" (where the triple step is replaced by a single step forming a slow, slow, quick, quick rhythm common to Foxtrot), and Double Swing (using a tap-step footwork pattern).

East Coast Swing is a Rhythm Dance that has both 6 and 8 beat patterns.[4] The name East Coast Swing was coined initially to distinguish the dance from the street form and the new variant used in the competitive ballroom arena (as well as separating the dance from West Coast Swing, which was developed in California). While based on Lindy Hop, it does have clear distinctions. East Coast Swing is a standardized form of dance developed first for instructional purposes in the Arthur Murray studios, and then later codified to allow for a medium of comparison for competitive ballroom dancers. It can be said that there is no right or wrong way to dance it; however, certain styles of the dance are considered correct "form" within the technical elements documented and governed by the National Dance Council of America. The N.D.C.A. oversees all the standards of American Style Ballroom and Latin dances. Lindy Hop was never standardized and later became the inspiration for several other dance forms such as: (European) Boogie Woogie, Jive, East Coast Swing, West Coast Swing and Rock and Roll.

In practice on the social dance floor, the six count steps of the East Coast Swing are often mixed with the eight count steps of Lindy Hop, Charleston, and less frequently, Balboa.

Basic technique

Single-step Swing

East Coast Swing has a 6 count basic step. This is in contrast to the meter of most swing music, which has a 4 count basic rhythm. In practice, however, the 6-count moves of the east coast swing are often combined with 8-count moves from the Lindy hop, Charleston, and Balboa.

Depending on the region and instructor, the basic step of single-step East Coast Swing is either "rock step, step, step" or "step, step, rock step". In both cases, the rock step always starts on the downbeat.

For "rock step, step, step" the beats, or counts, are the following:

Steps for the "lead" (traditionally, the man's part)

Steps for the "follow" (traditionally, the woman's part which mirrors the lead's part)Rock Beat 1 - STEP back with your LEFT foot Step Beat 2 - STEP forward with your RIGHT foot (to where you first started) Step Beat 3 - STEP to the left with your LEFT foot Beat 4 - Begin to shift your weight back to your right foot Step Beat 5 - STEP to the right with your RIGHT foot Beat 6 - Begin to shift your weight to the left and back

For "step, step, rock step," the rock step occurs on beats 5 and 6, but the overall progression remains the same.Rock Beat 1 - STEP back with your RIGHT foot Step Beat 2 - STEP forward with your LEFT foot (to where you first started) Step Beat 3 - STEP to the right with your RIGHT foot Beat 4 - Begin to shift your weight back to your left foot Step Beat 5 - STEP to the left with your LEFT foot Beat 6 - Begin to shift your weight to the right and back

The normal steps can be substituted with a triple step or double step "step-tap" or "kick-step" instead of a single step. This is commonly used during songs when a slower tempo makes the single step difficult (an example progression would be "rock step, triple step, triple step").

Timing

Because East Coast uses a six step pattern with music employing 4 beats per measure, three measures of music are required to complete two sets of steps, as shown in the following table.

The rock step starts on 1, 2 the first triple step starts 3a4 and the second on 5a6.Music beats (in fours): 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 Music beat incremental: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 East Coast Triple Step Timing: (1 and 2, 3 and 4, rock step) R S 3 a 4 5 a 6 R S 3 a 4 5 a 6 East Coast Single Step: (1 2 rock step) R S 3 5 R S 3 5

In single time style (used with faster music) the triple steps are replaced by single steps, so two beats of music are used for each single step while each step in the rock (R) step (S) is still completed in one beat, finishing the cycle in six musical beats. Some instructors will teach vocalizing the single time style as" "Quick. Quick. Slow. Slow. " or "Back Step. Slow. Slow."

There is the choice to start with triples or with a rock step, however if you check the above chart where a triple step starts on a 1, 2 you can see that the pattern progresses and wraps back around. The choice of starting with a triple or a rock step does have musical consequences as music has phrasing with hits that often happen on 12, or 24 or 36... This means that dancers who choose to start with a rock step you will probably find themselves on a rock step on every new phrase. Those who start with a triple will start with a triple on each new phrase. An advantage of starting with the triple step is that dancers can more easily change their foot work right at the start of the musical phrase.

See also

The Wikibook Swing Dancing has a page on the topic of: East Coast Swing References

- Dance Terminology Notebook. Skippy Blair. 1994. Altera. page 27. ISBN 0-932980-11-2.

- "Swing History origins of Swing Dance". 1996. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- "East Coast Swing History". n.d. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

04:30

04:30 SANKET MARSKOLE

SANKET MARSKOLE No comments

No comments

Hand jive

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia(Redirected from Hand Jive)This article is about the dance and songs referring to the dance. For the 1993 album by John Scofield, see Hand Jive (album).Not to be confused with Hand dancing.The hand jive is a dance particularly associated with music of the 1950s, rhythm and blues in particular. It involves a complicated pattern of hand moves and claps at various parts of the body, following and/or imitating the percussion instruments. It resembles a highly elaborate version of pat-a-cake. Hand moves include thigh slapping, cross-wrist slapping, fist pounding, hand clapping, and hitch hike moves.

In 1957 when filmmaker Ken Russell was a freelance photographer, he recorded the teenagers of Soho, London hand-jiving in the basement of The Cat's Whisker coffee bar, where the hand-jive was invented. According to an article in the Daily Mirror,[1] "it's so crowded the girls hand-jive to the band as there's no room for dancing." Russell told interviewer Leo Benedictus of The Guardian[2] that "the place was crowded with young kids... the atmosphere was very jolly. Wholesome... everyone jiving with their hands because there was precious little room to do it with their feet... a bizarre sight. The craze fascinated me. It seemed like a strange novelty; I used to join in."

Contents

Songs referring to "Hand Jive"

In April 1958, the label London released a song called "Hand Jive" by Bud Allen, performed by the Betty Smith Group. The song lyrics describe the hand dance the title refers to. Hand Jive by Betty Smith released April 1958

Capitol Records released the song "Hand Jive 6-5" in the U.S., backed with "Ramshakle Daddy" (3937) by British group Don Lang and the Frantic Five in March 1958 .[3] This recording does not feature the Bo Diddley rhythm.

The hand jive was popularized in the States by Johnny Otis's "Willie and the Hand Jive", described as a "funky blues rendition in a Bo Diddley styling" and "another approach to the growing Stateside interest in the British originated hand dance."[4]

This song exhibited the Bo Diddley beat, a rhythm that originated in Latin music and was brought into mainstream American music by Bo Diddley. It has since influenced generations of musicians.

Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis has a track named "Hand Jive" on his album Nefertiti from 1967.

Versions

Eric Clapton did a version of the Johnny Otis song in 1974 that reached the Top 40.[5]

Additionally, "Willie and the Hand Jive" was played on several occasions by the Grateful Dead and also by the New Riders of the Purple Sage with Jerry Garcia, Sony, 1972[6]

George Thorogood and the Delaware Destroyers recorded a version of "Willie and the Hand Jive" and a music video.[7]

Other uses: in music

The hand jive is also featured prominently in the Broadway musical Grease (1971) through the song "Born to Hand Jive"; in the movie adaptation of the musical, the song is performed by Sha Na Na. On a DVD audio commentary for the movie, choreographer Patricia Birch mentions that the dance also went by the much more risque name "hand job", but the title was changed as Grease was aimed at a family audience.

Jazz fusion guitarist John Scofield's 1993 album is called by [Hand Jive (album)]

The long-running Walt Disney World musical Festival of the Lion King (1997) uses this[clarification needed] during the song "Hakuna Matata," and the performers and audience do it while singing the song. The audience is taught the hand jive some time before the show begins.

The 2005 album "Midnight Boom" by the band The Kills features the hand-jive rhythm in the song "Sour Cherry." The band's goal while writing the album was to write rhythms inspired by old-school school-yard hand claps.

Beyond music

The term is also used by some jugglers in reference to certain hand motions in the Mills Mess juggling pattern.

See also

- Juba dance (hambone)

- Manualism (hand music)

- Bo Diddley beat

References

- Daily Mirror, 1 April 1957

- The Guardian, 8 January 2009

- Billboard Mar 17, 1958. Reviews of New Pop Records. page 34.

- Billboard Apr 28, 1958. Reviews of New Popular Records. page 34.

- Eric Clapton Top 40 Singles, archived from the original on 21 August 2006

- http://new.music.yahoo.com/new-riders-of-the-purple-sage/tracks/willie-and-the-hand-jive--1144532

04:27

04:27 SANKET MARSKOLE

SANKET MARSKOLE No comments

No comments

Jitterbug

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaFor other uses, see Jitterbug (disambiguation).The jitterbug is a kind of dance popularized in the United States in the early twentieth century and is associated with various types of swing dances such as the Lindy Hop,[1] jive, and East Coast Swing.Jitterbug dancers in 1938

Contents

Origin

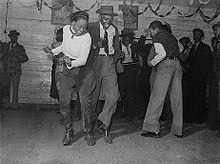

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) the word "jitterbug" is a combination of the words "jitter" and "bug";[2][3] both words are of unknown origin.[4][5][6]Jitterbugging at a juke joint, 1939. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott

The first use of the word "jitters" quoted by the OED is from 1929, Act II of the play Strictly Dishonorable by Preston Sturges where the character Isabelle says: "Willie's got the jitters" is answered by a judge "Jitters?" to which Isabelle answers "You know, he makes faces all the time."[4][7] The second quote in the OED is from the N.Y. Press from 2 April 1930: "The game is played only after the mugs and wenches have taken on too much gin and they arrive at the state of jitters, a disease known among the common herd as heebie jeebies."[4][8]

According to H. W. Fry in his review of Dictionary of Word Origins by Joseph Twadell Shipley in 1945 the word "jitters" "is from a spoonerism ['bin and jitters' for 'gin and bitters']...and originally referred to one under the influence of gin and bitters".[7]

Wentworth and Flexner explains "jitterbug" as "[o]ne who, though not a musician, enthusiastically likes or understands swing music; a swing fan" or "[o]ne who dances frequently to swing music" or "[a] devotee of jitterbug music and dancing; one who follows the fashions and fads of the jitterbug devotee... To dance, esp[ecially] to jazz or swing music and usu[ally] in an extremely vigorous and athletic manner".[7]

The first quote containing the word "jitterbug" recorded by the OED is from 1934 is the Cab Calloway song titled "Jitter Bug" and they quote the 1934 song printed in Song Hits magazine on 19 November 1939 as: "They're four little jitter bugs. He has the jitters ev'ry morn, That's why jitter sauce was born."[2]

Early history

Cab Calloway's 1934 recording of "Call of the Jitter Bug" (Jitterbug)[9] and the film "Cab Calloway's Jitterbug Party"[10] popularized use of the word "jitterbug" and created a strong association between Calloway and jitterbug. Lyrics to "Call of the Jitter Bug" clearly demonstrate the association between the word jitterbug and the consumption of alcohol:Dancing the jitterbug, Los Angeles, 1939

In the 1947 film Hi De Ho, Calloway includes the following lines in his song "Minnie the Moocher": "Woe there ain't no more Smokey Joe/ She's fluffed off his hi-de-ho/ She's a solid jitterbug/ And she starts to cut a rug/ Oh Minnie's a hep cat now."[11]If you'd like to be a jitter bug,

First thing you must do is get a jug,

Put whiskey, wine and gin within,

And shake it all up and then begin.

Grab a cup and start to toss,

You are drinking jitter sauce!

Don't you worry, you just mug,

And then you'll be a jitter bug!

Regarding the Savoy Ballroom, dance critic John Martin of The New York Times wrote the following:

The white jitterbug is oftener than not uncouth to look at ... but his Negro original is quite another matter. His movements are never so exaggerated that they lack control, and there is an unmistakable dignity about his most violent figures...there is a remarkable amount of improvisation ... mixed in ... with Lindy Hop figures. Of all the ballroom dances these prying eyes have seen, this is unquestionably the finest.[12]

Norma Miller wrote, however, that when "tourists" came to the Savoy, they saw a rehearsed and choreographed dance, which they mistakenly thought was a regular group of dancers simply enjoying social dancing.[13]

One text states that "the shag and single lindy represented the earlier popular basics" of jitterbug, which gave way to the double lindy when rock and roll became popular.[14]

A young, white middle-class man from suburban Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania learned to dance jitterbug in 1939 by going to the "Hill City" section of that city to watch black dancers. They danced smoothly, without hopping and bouncing around the dance floor.

The hardest thing to learn is the pelvic motion. I suppose I always felt these motions are somehow obscene. You have to sway, forwards and backwards, with a controlled hip movement, while your shoulders stay level and your feet glide along the floor. Your right hand is held low on the girl's back, and your left hand down at your side, enclosing her hand.[15]

When he ventured out into "nearby mill towns, picking up partners on location", he found that there were white girls who were "mill-town...lower class" and could dance and move "in the authentic, flowing style". "They were poor and less educated than my high-school friends, but they could really dance. In fact, at that time it seemed that the lower class a girl was, the better dancer she was, too."[15]

A number called "The Jitterbug" was written for the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. The "jitterbug" was a bug sent by the Wicked Witch of the West to waylay the heroes by forcing them to do a jitterbug-style dance. Although the sequence was not included in the final version of the film, the Witch is later heard to tell the flying monkey leader, "I've sent a little insect on ahead to take the fight out of them." The song as sung by Judy Garland as Dorothy and some of the establishing dialogue survived from the soundtrack as the B-side of the disc release of "Over the Rainbow".

Popularity

In 1944, with the United States' continuing involvement in World War II, a 30% federal excise tax was levied against "dancing" night clubs. Although the tax was later reduced to 20%, "No Dancing Allowed" signs went up all over the country. Jazz drummer Max Roach argued that, "This tax is the real story why dancing ... public dancing per se ... were [sic] just out. Club owners, promoters, couldn't afford to pay the city tax, state tax, government tax."[16]

World War II facilitated the spread of jitterbug across the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans. British Samoans were doing a "Seabee version" of the jitterbug by January 1944.[17] Across the Atlantic in preparation for D-Day, there were nearly 2 million American troops stationed throughout Britain in May 1944.[18] Ballrooms that had been closed because of lack of business opened their doors. Working class girls who had never danced before made up a large part of the attendees, along with American soldiers and sailors. By November 1945 after the departure of the American troops following D-Day, English couples were being warned not to continue doing energetic "rude American dancing."[19] Time reported that American troops stationed in France in 1945 jitterbugged,[20] and by 1946, jitterbug had become a craze in England.[21] It was already a competition dance in Australia.[22]

Jitterbug dancing was also done to early rock and roll. Rockabilly musician Janis Martin equated jitterbug with rock and roll dancing in her April 1956 song "Drugstore Rock 'n' Roll":

In 1957, the Philadelphia-based television show American Bandstand was picked up by the American Broadcasting Company and shown across the United States. American Bandstand featured currently popular songs, live appearances by musicians, and dancing in the studio. At this time, the most popular fast dance was jitterbug, which was described as "a frenetic leftover of the swing era ballroom days that was only slightly less acrobatic than Lindy".[26]

Blues musician Muddy Waters did a jitterbug during his performance at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, prompting massive cheers from the audience. His performance was recorded, and released on the LP At Newport 1960.

In a 1962 article in the Memphis Commercial Appeal, Bassist Bill Black, who had backed Elvis Presley from 1954 to 1957, and now the leader of the Bill Black Combo listed "jitterbug" along with the twist and cha-cha as "the only dance numbers you can play".[27]

See also

References

- Manning, Frankie; Cynthia R. Millman (2007). Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press. p. 238. ISBN 1-59213-563-3.

- "jitterbug, n. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "jitterbug, v. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "jitter, n. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "jitter, v.. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "bug, n.2 in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

Etymology unknown. Usually supposed to be a transferred sense of BUG n.1; but this is merely a conjecture, without actual evidence, and it has not been shown how a word meaning 'object of terror, bogle', became a generic name for beetles, grubs, etc. Sense 1 shows either connection or confusion with the earlier budde ; in quot. 1783 at sense 1 shorn bug appears for Middle English scearn-budde (-bude) < Old English scearn-budda dung beetle, and in Kent the 'stag-beetle' is still called shawn-bug. Compare Cheshire 'buggin, a louse' (Holland).

- Wentworth, Harold and Stuart Berg Flexner, ed. (1975). Dictionary of American Slang (2nd ed.). New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. p. 293. ISBN 0690006705.

1945: "[The term] is from a Spoonerism ['bin and jitters' for 'gin and bitters'] ... and originally referred to one under the influence of gin and bitters" H. W. Fry, rev. of J. T. Shipley's Dict. of Word Origins, Phila. Bulletin, Oct. 16. B22.

- According to The Oxford English Dictionary heebie-jeebie means "A feeling of discomfort, apprehension, or depression; the 'jitters'; delirium tremens; also, formerly, a type of dance."

- [1]

- site with photos and summary of the film

- "Wild Realm Reviews: Cab Calloway". Weirdwildrealm.com. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- Stearns, Marshall and Jean (1968). Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Macmillan. page 331. ISBN 0-02-872510-7

- Swinging at the Savoy. Norma Miller. page 63.

- Dance a While: Handbook of Folk, Square, and Social Dancing. Fourth Edition. Harris, Pittman, Waller. 1950, 1955, 1964, 1968. Burgess Publishing Company. No ISBN or catalog number. page 284.

- Stearns, Marshall and Jean (1968). Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Macmillan. page 330. ISBN 0-02-872510-7

- Stomping the Blues. By Albert Murray. Da Capo Press. 2000. pages 109, 110. ISBN 0-252-02211-4, ISBN 0-252-06508-5

- Popular Science, January 1944. "The Seabees Can Do It". page 57.

- Ambrose, Stephen (1994). D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New York: Touchstone. p. 151. ISBN 0-671-67334-3.

- Billboard, 24 November 1945. "Britons Drive to End Jiving as Yanks Go Home". page 88

- "U.S. At War: G.I. Heaven". Time. 18 June 1945.

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcfour/lostdecade/timeline_html.shtml

- Sydney Morning Herald article, "Muscle beach party", by Steve Meacham, 8 Jan 2009

- http://rcs-discography.com/rcs/artists/m/mart5200.htm

- http://www.rockabilly.nl/lyrics1/d0016.htm

- http://rcs-discography.com/rcs/ss/02/ss2800.mp3

- Shore, Michael; Dick Clark (1985). The History of American Bandstand. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 12, 54. ISBN 0-345-31722-X.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)